A postcard from hell

Extreme heatwaves are the new normal, and they’re changing our gardens for ever

You’re reading The Earthworm, an alternative gardening newsletter that takes a sideways look at the world of gardens, gardening, horticulture and all that good green stuff. If this is your first time here, you can catch up on anything you’ve missed by following this link. Subscribe now for free and join the community or, if you can afford to do so, support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription at any time. Thanks, and enjoy today’s post.

We Brits love to talk about the weather. I loathe lazy stereotypes and unhelpful caricatures, but I’m sorry, in this case, it turns out it’s genuinely possible to characterise an entire nation – all 67 million-plus of its inhabitants – with this catch-all cliché.

Outside the nursery gates, at the supermarket checkout, crossing paths with a neighbour, literally any time, any place, with any one, the conversation within a matter of seconds will turn to what the weather has just been, now is, or is supposed to be about to become.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence then that Britain is also a nation of gardeners. You can be a weather bore and not be a gardener, I suppose, but how many gardeners out there don’t care deeply about the weather? The recipe for creating a successful garden is, after all, equal parts soil and climate, with plants to garnish.

Anyway, things this week got out of hand. This past Tuesday evening, a heatwave of unprecedented proportions reached its sweltering peak. Many parts of the UK recorded their highest ever temperatures. As in, ever ever. (Or at least, since people started taking note of these things.) Here in the South East, the mercury hit 40°C (104°F) for the first time.

Now, some of my readers, in Spain or the American South, for example, might shrug their shoulders at these numbers. “Welcome to our world,” they may say. The difference is, Britain isn’t built for those sorts of temperatures. We have no porches or porticoes, wall-mounted AC units or external shutters. Our buildings are not summer hardy, and neither are our people.

Crucially, we lack the collective cultural knowledge of how to cope. I know that Madrid, for example, becomes a sort of ghost town during the peak of the summer heat, as residents flee to the coast. It’s not uncommon for workers to take the entire month of August off, using up all of their holiday allowance in one life-saving swoop. Madrileños are smarter than to try to fight climatic conditions; it’s a far better strategy to take flight.

The terrifying thing, of course, is that this summer’s heatwave (currently on hiatus, but expected to return next month for a comeback tour), isn’t just a freak event, but the start of a new normal. The wildfires, the melting tarmac, the strain on the health service, are all due to become worryingly constant features of our British summers, as they already are elsewhere. That’s what the climate scientists warn and, to be frank, at this stage, you’d have to be an actual certified idiot not to believe them.

The toll on human health is likely to be severe, and can’t be underestimated. But this is a gardening newsletter, so I hope you’ll forgive me for switching focus to our vegetable friends.

Because it’s not just our homes that aren’t designed to cope with hot, dry summers, but our gardens too. According to the RHS, the days could be numbered for many of our traditional border-filling favourites. Roses, hydrangeas and acers have all taken an absolute battering in recent days, and might start disappearing altogether – either because the sun will kill them, or due to the preemptive action of risk-averse gardeners.

We’re used to talking about how hardy plants are, or which growing zone we’re in, but these things only describe how much cold a plant is able to tolerate. Well, we might have to come up with an equivalent for heat.

I have to say, my garden has fared encouragingly well. There have been plenty of victims, don’t get me wrong. A fair few seedlings and cuttings have withered and died, my daily pot-watering unable to keep them suitably hydrated; the delicate, deep-purple leaves of my acer have turned rusty; and parched patches of yellow and brown have formed on the foliage of my hydrangea. And elsewhere, the worst may be yet to come – it can apparently take up to a week for the full effects of heat damage to be seen.

And still, the overall effect out there is one of colourful vigour. Not because I’ve flooded the borders with water – like I said in a recent post, I tend not to water the borders at all, unless a particular plant looks to be in particular need. No, my garden looks alright because I’ve accidentally filled it with heat-hardy immigrants.

Dahlias originate in Mexico; salvias, today ubiquitous, have their evolutionary roots in the Mediterranean; cannas grow wild in the tropics, in both North and South America; and crocosmias hail from sunny South Africa. I planted all of these things in my sunny border not because I’m a climate-proofing genius, but because I love them. I love their shapes, their contrasting foliage, their reliability, and most of all I love their colours, which pop and zing and burst and sing all the way through mid-late summer.

Planning ahead – like, way ahead – is tricky, not to say impossible. Our garden plants here in the UK, we’re told, will need to be able to tolerate extended periods of hot, dry weather during summer, but also long wet winters. Some of our current stalwarts might turn out to be just fine, in the peculiar microclimate of any given back yard; others will not.

Lists of future-proof plants will be published and shared, and words like “drought tolerant” or “heatwave hardy” might begin to appear alongside “pollinator friendly” on labels. But just as we’re still figuring out how to keep our homes – and ourselves – relatively cool during a hell-ish English heatwave, nothing can really, fully prepare us for how to cope with the horticultural impact of the climate crisis. It’s something we’ll all just have to work out as we go.

But if you don’t already, you’d better learn to love salvias.

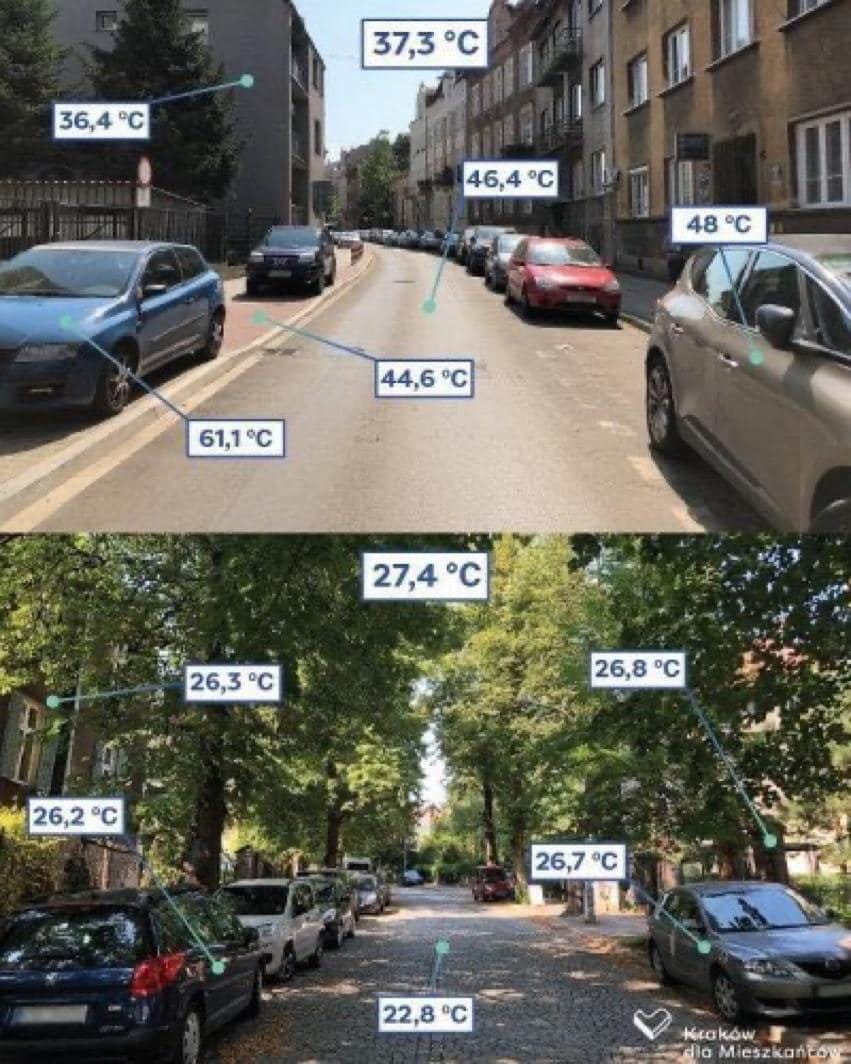

While we’re on the subject of heat, I shared an image on my Instagram stories the other day that seemed to really resonate with people – as it did with me, hence why I re-posted it from another account.1

The picture above depicts scenes and relative temperatures from two neighbouring streets in Krakow, Poland, on the same day. One street is covered by a lush canopy of mature trees, and the other one… isn’t. The cooling effect of street trees – and of green spaces versus grey ones – is somehow both obvious and incredible.

Most of us don’t have a huge amount of sway when it comes to whether street trees are planted in our areas, but what we can do is make sure that the ones that are already there – particularly saplings – are given every opportunity to reach maturity. If you can get out and water a street tree, please do. And if you’re unsure whether or not one or more of your neighbours is already watering it, don’t worry – there is zero chance of you over-watering a tree right now.

I originally saw this comparison of Krakow road temperatures on Twitter, posted by the so-called Cycling Professor. Greenpeace UK shared a similar image on Instagram, which you can see here.

I'm dealing with the change in weather here in Sweden too. We had an exceptionally cold spring and summer with intermittent heat bursts. So the vegetables that did manage to grow in the cold suddenly struggled with drought and heat. Not much of our harvest this year. It's hard to find plants that are able to deal with both.

Well. We are used to extreme heatwaves here in Florida USA! It happens every summer. I feel like I'm living in The Day of the Triffids. Help!